It Happened Here: Trafficking of Boys and Men

Dec 3, 2025

I was in my twenties the first time I went to one of Bryan Singer’s pool parties in the Hills. It was everything you’d expect from a director’s estate: palatial, expensive, exclusive. Inside the kitchen, my friend—who had once been Singer’s underage boyfriend and was now a young adult enjoying his financial support—was laughing with him over a bottle of wine, totally at ease. Outside, you could hear the splash of the pool, the slurred joy of boys too young to be drunk, and the kind of nervous laughter that fills the air when something isn’t right, but no one wants to say it. My friends and I brushed it off with jokes and eye-rolls. “That was just the scene”, we said.

But when I got home, and even more as I got older, the unease calcified into something harder. I realized I hadn’t just witnessed something disturbing—I had been part of the environment that allowed it. Human trafficking doesn’t always look like a movie plot. Sometimes it looks like silence. Sometimes it looks like us.

When silence becomes part of the system

Human trafficking thrives where power goes unchecked—and West Hollywood, despite its progressive ideals, has been both a haven for survivors and a blind spot for abuse.

Globally, the scale of modern trafficking is staggering:

50 million people are estimated to be living in modern slavery worldwide

6.3 million are victims of forced commercial sexual exploitation

In the U.S., 24,000 victims were identified in 2024.

California leads the nation in reports, with Los Angeles County consistently among the top trafficking hubs

Men, boys, LGBTQ+ youth, and unhoused individuals are routinely undercounted and underserved

These numbers are not distant. In West Hollywood—where politics, entertainment, nightlife, and survival intersect—trafficking often hides in plain sight. Sometimes it hides behind charm. Sometimes behind celebrity.

Epstein: the “out-of-reach predator” problem

The renewed uproar over the Epstein files is a case in point. The Trump administration’s Department of Justice stalled the release of key documents, and U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi recently confirmed that Donald Trump is named within them. But the issue isn’t just who knew Epstein. It’s what he represented: a pattern of abuse by what anti-trafficking experts call out-of-reach predators—powerful individuals protected by institutions, reputation, and the legal system itself.

The reported death of Virginia Giuffre in April, allegedly by suicide, was heartbreaking. As the most well-known survivor to come forward in the Epstein-Maxwell case, she had fought for years to expose their network. But those close to her say her personal life had spiraled—after a painful divorce and a lifetime of retraumatizing litigation. Her story is tragic, but not uncommon. Many survivors of organized abuse die quietly, not at the hands of their abusers, but in the long shadow of what was done to them.

Epstein’s alleged ties to intelligence agencies only deepen the darkness. Former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida Alex Acosta reportedly told colleagues he was instructed to “back off” Epstein’s case in 2007 because Epstein “belonged to intelligence.” Ghislaine Maxwell’s father, Robert Maxwell was widely known to have worked with Israeli intelligence. These details, once dismissed as conspiracy theory, are now accepted by many as likely. And still, no full reckoning has come.

It’s not just Epstein: other elite trafficking scandals

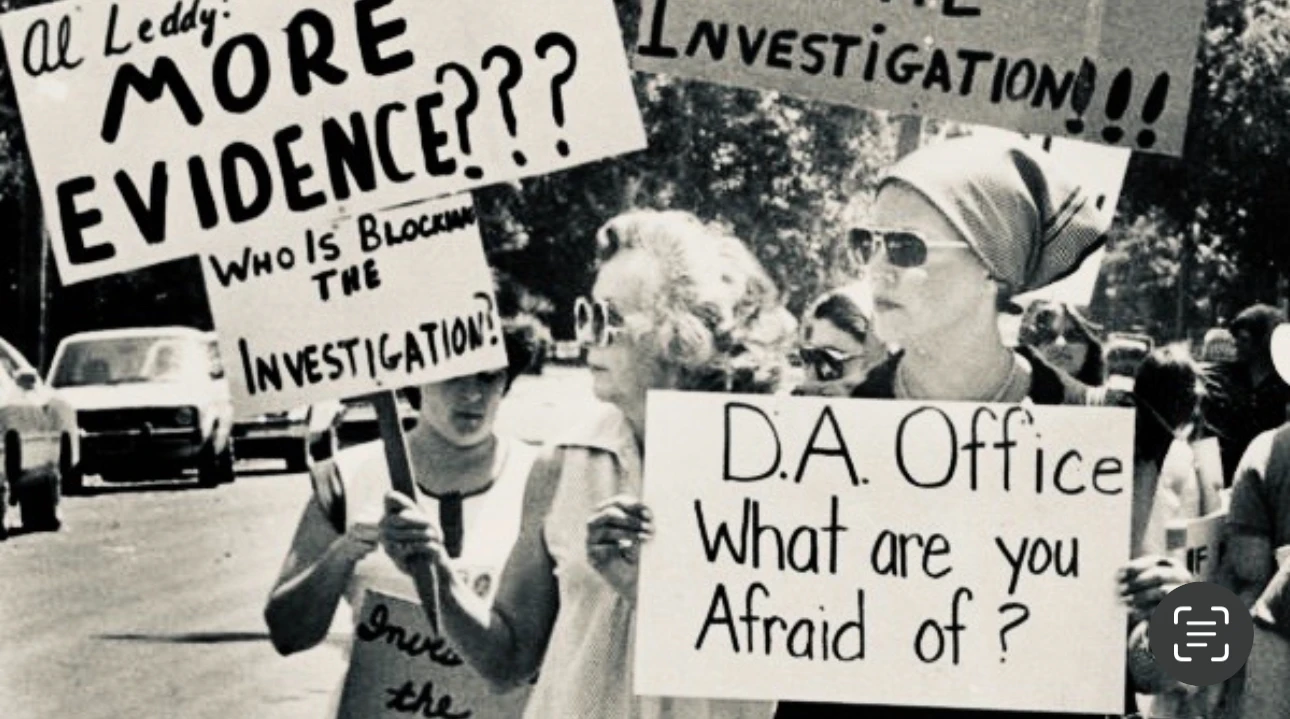

Demonstrators protest alleged cover-ups in the Lords of Bakersfield trafficking ring

The United States has seen other examples.

The Franklin Credit Union scandal in Omaha in the 1980s involved the alleged trafficking of underage boys to wealthy and politically connected men. Larry King, who ran the credit union and facilitated the network, was convicted in 1991 of embezzling approximately $39 million from the credit union, and sentenced to 15 years in prison (serving about 10). Meanwhile, many alleged buyers and collaborators walked free.

In 1981, during the unmasking of the politically connected Lords of Bakersfield trafficking ring, one teenage victim, Robert Mistriel, was convicted of killing his trafficker and served 38 years in prison. He is now suing Kern County and Catholic Charities for allegedly facilitating his abuse while in their custody.

Another historical example often cited is the Finders cult, investigated in the 1980s for suspected child trafficking and ritual abuse. According to buried government documents and reporting, the group’s case involved disturbing materials and was allegedly protected by the CIA—adding to the broader pattern of institutional complicity in organized abuse.

Across the Atlantic in the UK, a paedophile dossier naming MPs and other politically connected elites was handed to Scotland Yard in the 1980s—only to later vanish, raising long-standing fears of a government cover-up.

And in Belgium, the Marc Dutroux affair exposed a network that trafficked young girls and boys to elites and included acts of torture, murder and sadistic abuse. Despite overwhelming evidence, many of Dutroux’s high-level collaborators were never prosecuted, sparking massive protests and public outrage.

In 2021, West Hollywood resident and Democratic donor Ed Buck was convicted in federal court on all seven felony counts, including supplying methamphetamine that led to the deaths of two Black men. While not charged with trafficking, his pattern of luring vulnerable, unhoused victims into his home, injecting them with drugs, and evading consequences for years fits the same mold: power shielding abuse.

The Bryan Singer culture problem

Bryan Singer has denied multiple allegations of exploitation of underage boys.

And then there’s Bryan Singer.

Like many young gay men in West Hollywood, I attended the parties. I saw the dynamics. Some of the boys were underage. There were drugs, alcohol, and an unspoken understanding that certain lines weren’t really lines if you were close enough to fame. Some of those boys “made it” and still defend the experience. Others filed lawsuits. At least one retracted. One was found dead in a hotel room.

To be clear, Singer has denied all allegations. But what matters here is the culture that made it all possible. A culture I participated in. A culture where adult-teen dynamics were normalized, glamorized even, especially when money and social access were part of the deal. That culture still exists. And it doesn’t always feel like exploitation—until it does.

Trafficking isn’t only “the rich and notorious”

But trafficking in West Hollywood isn’t limited to the rich and notorious. When I worked with the Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking (CAST), I launched a campaign focused on male survivors. I quickly found what most outreach programs miss: many of the young men navigating homelessness and survival sex in and around West Hollywood had experienced trafficking conditions—often involving coercion, manipulation, or survival pressure that met the federal definition of trafficking: force, fraud, or coercion.

According to Federal data, labor trafficking involving males accounts for the majority of all human trafficking cases in the United States. And while male survivors of sex trafficking exist in large numbers, they are chronically underreported and underserved due to stigma, criminalization, and disbelief. As the GROW counseling center puts it, trafficking doesn’t just happen to girls. Men and boys are victims too—especially those who are economically, socially, or psychologically vulnerable. Yet public messaging, funding, and services rarely reflect that reality.

What our LGBTQ+ community has to confront

Male survivor advocates rally in WeHo during a #MeToo-era demonstration.

LGBT communities are in a unique position—and carry a unique responsibility.

We are a community that prides itself on progressivism, on compassion, on queerness. But if we want to live up to those values, we must act with clarity, humility, and courage.

That means demanding real accountability for predators—no matter how well-connected or charming they may appear. It means changing the culture within our own LGBTQ+ community, where adult–teen “mentorships” and power-imbalanced relationships are too often excused as rites of passage. It means creating clear boundaries and a zero-tolerance stance on exploitation masquerading as social access.

It also means funding services that meet people where they are—not just “ideal” victims, but those surviving on the margins. Many people in the sex trade are doing what they can with the choices available to them. Supporting them means decriminalizing their survival, offering real exits, and protecting their agency—not punishing it.

And most urgently, it means tailoring anti-trafficking efforts to include men and boys—not as an afterthought, but as a central focus. We need culturally competent outreach, support groups, and prevention strategies that reflect the realities of LGBTQ+ youth, street-involved men, and others who don’t fit the public’s narrow image of a trafficking victim.

Whether it’s a teenager trafficked through a network of billionaires or a boy passed around in the alleys behind Santa Monica Boulevard, every victim matters.

Every survivor matters

On July 30th, the world marked World Day Against Trafficking in Persons—a day to raise awareness, honor survivors, and demand action. Communities can do more than observe it. We can course-correct. We can own our blind spots. And we can lead—by building a community that centers truth, survivor dignity, and cultural transformation from the inside out.

Get Involved!

Have a question, a project idea, or a situation you’re trying to make sense of? Reach out. We’ll point you toward next steps—whether that’s training, consulting, collaboration, or the right support.